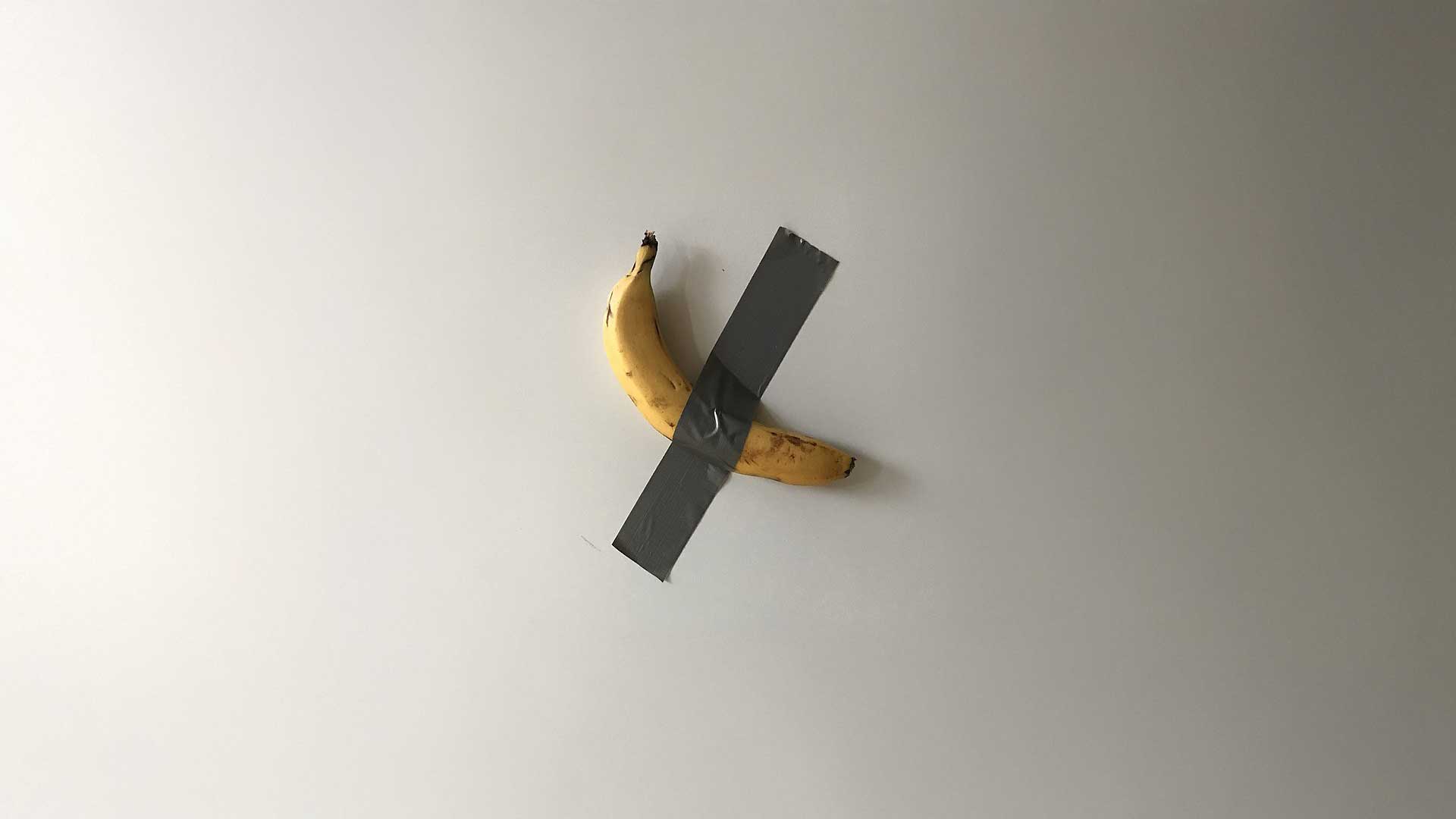

What makes a work of art valuable? Is it the emotional resonance of a Monet landscape, the revolutionary structure of a Picasso portrait, or the sheer audacity of a banana duct-taped to a wall? Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian, recently sold for a staggering $6.2 million at Sotheby’s in New York, has reignited this perennial question, thrusting the art world into yet another debate about what art is—or isn’t.

At its core, Comedian is both an object and an idea: a conceptual statement about art’s commodification and absurdity. Yet, it’s also a mirror reflecting contemporary society’s fascination with spectacle. In this critique, we’ll unravel the layers of meaning—or lack thereof—embedded in works like Cattelan’s banana and explore whether they elevate art or merely exploit its mysterious power to fascinate, mystify, and transmute.

A Banana Among Giants

Comparing Comedian to works by Monet or Picasso feels almost sacrilegious, yet the contrast is instructive. Monet’s Water Lilies immerse us in light, texture, and time, embodying Impressionism’s attempt to capture fleeting moments of beauty. Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, meanwhile, dismantles classical conventions, creating a fragmented, visceral representation of modernity’s anxieties.

Cattelan’s banana, however, offers no such sensory or historical richness. It is ephemeral by design: a piece of fruit destined to rot, replaced by another identical banana. The work relies entirely on context—the auction house, the media frenzy, the whispers of billionaires bidding millions—not on any inherent aesthetic or emotional quality.

Yet, herein lies its genius, if we dare call it that. Cattelan doesn’t just create art; he creates an event. His banana is a provocation, daring us to ask: Who decides what art is? Who decides its value?

Art or Antics? The Thin Line of Conceptual Work

“Banana duct taped to fridge as a reminder to eat less meat,” by Andrew Butko, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The rise of conceptual art in the 20th century challenged traditional notions of skill and beauty. Works by Duchamp (Fountain, 1917) and later Yoko Ono (Cut Piece, 1964) transformed art into an intellectual exercise, placing greater emphasis on ideas than on materials or craftsmanship. Cattelan’s Comedian follows this trajectory, though it arguably reduces conceptual art to its most marketable form: shock value.

This reduction, critics argue, risks trivializing art’s profound potential. Comedian thrives on its absurdity but offers little beyond it. Unlike Duchamp, whose ready-made urinal questioned institutional gatekeeping, or Ono, whose performance invited audience participation, Cattelan’s banana is, ultimately, a prop. It depends on the market’s complicity and the public’s outrage to sustain its relevance.

A Veil for Money Laundering? The Shadow of the Market

Critics of such works often point to the opacity of the art market as a potential explanation for their inflated values. Unlike stocks or real estate, artworks are unique assets with subjective pricing, making them ideal instruments for wealth transfer or money laundering. High-profile sales like Comedian feed suspicions that contemporary art can sometimes serve as a smokescreen for financial maneuvering.

However, dismissing conceptual art as merely a vehicle for market manipulation overlooks its cultural resonance. Comedian speaks to our hyper-consumerist moment, where even the absurd becomes a commodity. The banana taped to a wall is not just a banana; it is a symptom of a society where spectacle trumps substance, and the market dictates meaning.

The Broader Trend: Art in the Age of the Meme

Cattelan’s banana also exemplifies a broader trend: the meme-ification of art. In an age of social media, artworks are increasingly designed for virality, their success measured in clicks and shares rather than aesthetic impact. This shift raises urgent questions about art’s future.

Does the ubiquity of images dilute art’s power, or does it democratize access to culture? By reducing a work to a punchline, do we rob it of depth, or do we engage with it in new, dynamic ways? Cattelan’s banana lives at this intersection, a meme and a market darling, a joke and a critique, a banana and…something more?

What Does This Mean for Art?

In many ways, Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian is a perfect artwork for our time. It is absurd, fleeting, self-aware, and shamelessly tied to the market’s machinations. It forces us to confront uncomfortable truths about the art world and ourselves: our willingness to be dazzled by spectacle, our complicity in upholding inflated values, and our craving for narratives that transcend the mundane.

But is it great art? That depends on whether you believe art should inspire beauty and introspection or challenge and provoke. Either way, Comedian ensures one thing: the conversation about art’s purpose, value, and meaning will continue. And perhaps that, more than the banana itself, is what matters most.